Richard Lance Keeble

Withcall is a Lincolnshire Wolds village situated in a secluded valley five miles south west of Louth and fifteen miles from the sea. The surrounding hills rise to 550ft and, at nearby Normandby le Wold, are the highest land on the east coast north of Dover and up to Yorkshire. The Wolds area as a whole has been designated an ‘area of outstanding beauty’. The chalk cap to the hills is nowhere more than about 300 feet thick: below is a series of relatively thin sandstones, ironstones and clays, and below them a more resistant sandstone, all on a thick base of clay.[1]

Bluestone Heath Road, a delightful approach to the village, provides an ever-changing panorama of the rolling hills and a close-up view of the mast of the (now disused) Stenigot wireless station.[2]

The Romans – and then Normans – Arrive

The name Withcall is derived from its Roman name Vita cala, the area being occupied by Romans from AD82-410. By 1066, following the Viking invasion, begun in 793, the village was known as Vio-Kior.

The Vikings were ejected from the country following their defeat at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in 1066 (just before William of Normandy’s victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October of the same year). And by 1086 land in the Withcall area was owned by Bishop Odo of Bayeux, the maternal half-brother of William the Conqueror, who was for a period second in power after the King of England.[3] The Bayeux Tapestry is thought to have been commissioned by Odo to be hung at his cathedral. Interestingly, the tapestry does not depict him fighting but encouraging his soldiers from the rear. William’s Doomsday Book, of 1086, a grand survey of the country to assist in the levying of taxes, recorded 300 inhabitants in the village.

During the seventeenth century, a lot of the surrounding land was turned over to sheep grazing. Joan Thirsk, in her England Peasant Farming, of 1957, reports the Lord of Withcall ‘was preparing in 1681 to change the Westfield from crop-growing to the keeping of sheep’.

Withcall House dates from around 1830 though a number of extensions have been added subsequently while the Old Rectory in the village was designed by S. S. Teulon and dates from 1849.[4]

Clayton’s Experiments with Mechanised Farming

In 1880, the Withcall estate was owned by Nathaniel Clayton (1811-1890) who, with his brother-in-law, Joseph Shuttleworth (1819-1883), set up the Clayton and Shuttleworth engineering company in Lincoln in 1842. They began constructing portable steam engines in 1845 and presented their work at the Great Exhibition of 1851. They soon became one of the leading makers of agricultural machines in the country.[5]

Clayton treated the Withcall estate as ‘an experiment in highly capitalized and mechanized farming’. Robinson reports one contemporary commentator: ‘Large flocks of fine Lincoln, long wooled sheep are bred and fed on turnips and grass seed and numbers of large shorthorned castle are bred and fed in the yards during the winter on roots, cake, corn and straw. By pursuing this system of farming the Wolds are kept in the highest state of cultivation that such a soil can be: they are made to produce magnificent crops of turnips, and they turn out a class of sheep which have long been famous.’[6]

The roadway through the hills to North Farm was dug and a modern water system was installed – serving the whole estate. Eric Newton writes:

The source of the water was a series of springs in the north-east corner of the parish. Water was also impounded there to form a large reservoir which gave a supply to drive a waterwheel. This in turn drove a 3-cylinder pump to drive the fresh spring water along cast iron pipes to holding tanks at several farmsteads around the estate.

The length of piping was considerable (over 6 miles) and the height between pump and storage tanks was also remarkable (over 200 feet, in one instance). The private system worked – almost maintenance free – until the public piped water supply reached the village in the 1970s.[7]

Clayton also had the village school built while the Church of St Martin, dedicated to St Martin of Tours and designed by Sir Arthur Blomfield (1829-1899), was erected in 1882 after a fire in 1880 destroyed the previous building. All the windows are in Early English lancet style: the west window has modern glass showing St Martin as a warrior and a bishop, with scenes of him sharing his cloak with the beggar and converting the robber in the mountains. In the rose window above there is a fine picture of Tours cathedral.[8]

Elizabeth (1781-1665), the mother of Alfred Lord Tennyson, Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria’s reign, was the daughter of Stephen Fytche (1734-1799), vicar of St. James’ Church, Louth (1764), and rector of Withcall (1780). She was baptised at the church.

Arrival of the Railway Era

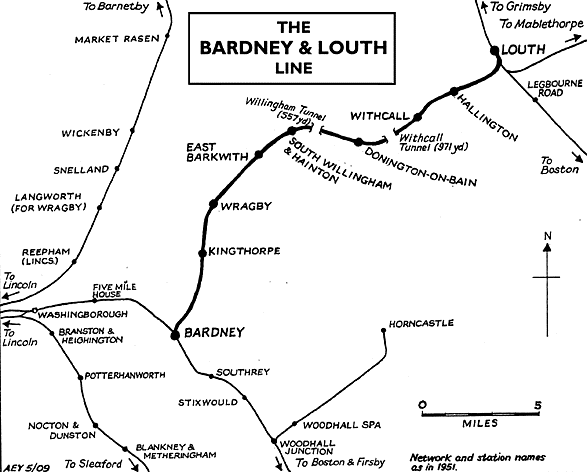

In the late nineteenth century, a railway line was constructed from Bardney to Louth as part of a single track Lincoln to Louth line. The Louth and Lincoln Railway company was launched at a meeting in the King’s Head Hotel, Louth on 3 November 1865 but lack of money caused the directors to apply to parliament to abandon the project. Permission was not granted and a civil engineer, based in Manchester, Frederick Appleby, took on the project. He shortened the line and reduced the worst gradients by adding tunnels at Withcall and South Willingham. Construction started in July 1872. The Withcall station was the second one west of Louth on the line. Building of the 971-yard tunnel (now abandoned to bats) to cut through the hills at Withcall began in January 1872 (the tunnel at nearby South Willingham is shorter). Adrian S. Pye writes: ‘Construction was delayed by bad weather and in October 1874, a deluge of water washed navvies out of the tunnel. Bricklayers went on strike because their hands were being scalded by wet lime and December saw the death of a workman [Cornelius Janaway} who was struck by a wagon.’[9]

The line opened for goods on 28 June 1876 and on 1 December 1876 for passengers. Ludlum and Herbert write: ‘The original passenger service consisted of five trains each way on week days only. This was reduced to four trains by January 1877, only a month after services began. South Willingham was renamed South Willingham and Hainton and Donnington dropped an “n” and became Donington. A siding was opened at Withcall in July 1878 followed, a month later, by a small station manned by a solitary station master which help from a youthful porter in the “agricultural season”.’[10]

But the line struggled financially and, in 1881, went into receivership. The Great Northern Railway company purchased it later that year for about half of its building costs.[11]

The tunnel has been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) by Natural England because of its bats population and is one of 98 SSSIs in the county.[12]

The train line played an important role during the Second World War. As Hancock records: ‘In the first four years of the war the bombs for the Lancasters came from dumps in the west of the county, but in January 1943 Market Stainton Hall and its grounds, plus fields in the locality, were taken for bomb storage by 233 Maintenance Unit. The bombs were delivered by road and rail, via Withcall and Hallington stations. Ammunition was also stored along the grass verges and lanes around the villages, often unguarded.’[13]

old1.jpg)

The line for passengers was closed on 3 November 1951. Driven by Mr Bill ‘Bumper’ Cartwright, of Tennyson Road, Louth – with Mr Fred Hardy, of St Bernards Avenue, Louth, the fireman and the guard Mr Cyril Thompson, of Lincoln Walk, Louth – the train was an old GN C12 No. 67379. The journey started at 3.57 pm from Louth with about 50 passengers on board. At Wragby, stationmaster E. C. Savony presented a wreath of white and bronze chrysanthemums to driver Cartwright on behalf of the station staff. … The return to Louth began in heavy rain. … All through the journey the strains of “Auld Land Syne” were heard from the coach in which the Gainsborough Model Railway Society travelled. … A considerable crowd had gathered at Louth for the arrival of the 7.21 from Bardney. The C12 arrived dead on time. People crowded around the engine intent upon getting the autographs of the crew.’[14]

The goods line was terminated on 17 December 1956 (thus pre-dating the infamous Beeching cuts of the 1960s).

Withcall’s tiny wooden station continued for a while as a Methodist chapel until being demolished in the mid-1980s. A metal plaque commemorates the station but it has the date wrong for the opening.

The Fatal 1920 Flood

On 29 May 1920, Withcall was the main site of the cloud burst that led to the River Lud flooding Louth, killing 23 people in 20 minutes and washing away rows of houses. It is considered one of the worst flood disasters in Britain in the 20th century.

Withcall – and Stenigot – in World War Two

In 1938, work began on constructing the radar masts at Stenigot, one of the first radar stations in the world. Completed in the following August, the four 360 feet high steel transmitter towers and four 280 feet high wooden receiver towers came to dominate the local scenery. The Air Ministry called them Radio Direction Finding Stations which the public – and Germans – seemed to accept. The station official title, Air Ministry Experimental Station Type 1, provided no indication of its real purpose.[15] Terry Hancock reports: ‘They were one of 20 original Chain Home long-distance radar stations in a chain from the Isle of Wight eastwards and northwards around the coast to guard against German bombers. Their value to the defence of Britain cannot be over-estimated. They sent out radio beams in a 120 degrees arc to a distance of some 100 miles to detect approaching enemy aircraft. The 140 operation personnel were housed in a small hutted camp to the east, at New Buildings near Withcall.’[16]

On 18 September 1944, two Polish air crewmen died at Withcall after the Mosquito they were flying crashed after colliding with another plane returning on Operation Market Garden from Arnhem, in the Netherlands. The pilot Stanislaw Roman Madej, aged 27, and the navigator, Zojef Stanislaw Gasecki, aged 25, were buried at the Polish war graves cemetery, Newark. A memorial to them was unveiled on 27 September 2016, by Mr Henry Smith, of Home Farm, Withcall, in the field close to the old Louth to Bardney rail line where they crashed.[17]

Home Farm Today

Home Farm has won a number of prestigious awards for conservation (since it mixes both arable and stock farming) and has also led the way in introducing many new forms of agricultural technology. The farm is also the site of a farm machinery museum while another museum (viewable only through private arrangement) features historic artifacts – some of them dating back 300 million years.

Notes

[1] David Robinson, The Shaping of the Wolds, in The Lincolnshire Wolds, edited by David N. Robinson, Oxford and Oakville: Windgather Press, 2009 p. 1

[2] The King’s England: Lincolnshire, London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1949 p. 427

[3] A warrior and statesman, Odo is believed to have been born in 1035 and died in 1097. Duke William made him Bishop of Bayeux in 1049. He acquired vast stretches of land in some 23 counties, mainly in the south east and East Anglia

[4] Nikolaus Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Lincolnshire, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002 p. 808

[5] By 1870 the company had made 10,000 portable steam engines, with an output of three a day. Small branches were set up in Austria and German and by 1900 they were employing 2,000 men. But following the 1914-1918 war, their markets in Europe collapsed and by 1930 Marshall had acquired the agricultural assets of the company. See Richard Brooks and Martin Longdon, Lincolnshire Built Engines, Lincolnshire County Council, edited by Lesley Colsell, 1986 p. 4

[6] Charles Rawding, High Farming on the Wolds, in The Lincolnshire Wolds, edited by David N. Robinson, Oxford and Oakville: Windgather Press, 2009 pp 44-45

[7] See https://hbsmrweb-lincolnshire.esdm.co.uk/Source/SLI15211

[8] The King’s England: Lincolnshire p. 427

[9] See https://schools.geograph.org.uk/photo/6514009#:~:text=Now%20abandoned%20to%20bats%2C%20work%20on%20Withcall%20Tunnel,of%20water%20washed%20navvies%20out%20of%20the%20tunnel

[10] A. J. Ludlam and W. B. Herbert, The Louth to Bardney Branch, Oxford: Oakwood Press 1987

[11] Alan Stennett, Lincolnshire Railways, Marlborough, Wiltshire: The Crowood Press, 2016 pp 52-54

[12] See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Sites_of_Special_Scientific_Interest_in_Lincolnshire

[13] Terry Hancock, The Wolds at War, in The Lincolnshire Wolds, edited by David N. Robinson, Oxford and Oakville: Windgather Press, 2009 p. 72

[14] W. B. Herbert and A. J. Ludlam, The Louth to Bardney Branch, Oxford: Oakwood Press, 1984 pp 33-34

[15] Terry Hancock p. 69

[16] A. J. Ludlam and W. B. Herbert, The Louth to Bardney Branch, Oxford: Oakwood Press 1987 p. 13

[17] See http://www.slha.org.uk/photogallery/?thislocation=Withcall#apm1_2